A review for Kirsty Hendry, Collective

Navel Gazing, Kirsty Hendry

Collective Satellites Programme

24 Oct 2020 — 22 Nov 2020

Kirsty Hendry’s new film presents a defense of the body’s interior visceral matter. The film, with its theatrical overtures, imagines the body’s organs as intuitive, autonomous, intellectual and political, as independent sites of knowing. Each organ’s gelatinous vocabularies sound out the noise of insurgency. A transgressive demand for recognition. Organic anatomies orate opposition and describe an alternative to the mind’s rational intentions. Your body is a battleground.

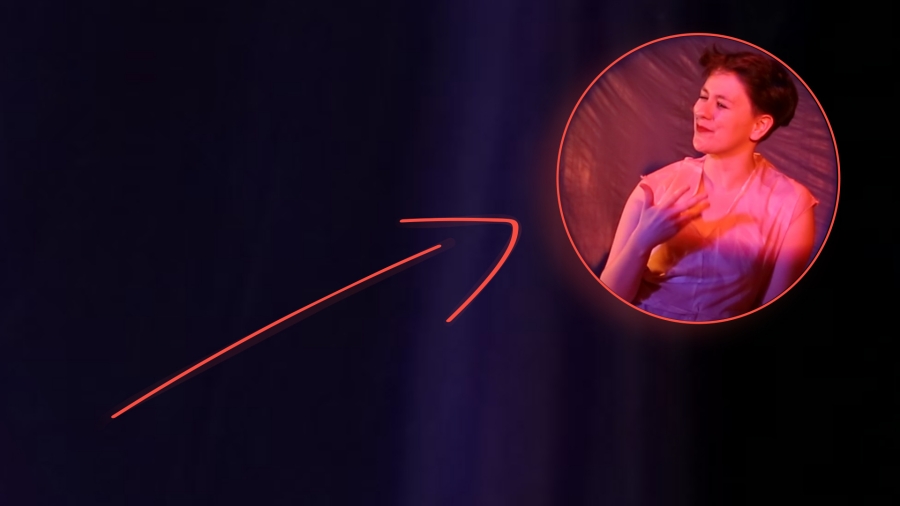

Organized around a series of monologues performed by dance and theater artist Aby Watson the film, richly toned in hues of violet, puce and mauve, onomatopoetically ruminates on the sound of bodies, utterance within the body, utterance emanating from the body, a soundtrack of ingestion and evacuation evidencing ideas of auscultation, vulnerability and penetrability and sites its principal drama within the gut where its bacteria, archaea and fungi congress as a horde of intuition, wisdom and prophesy. This chimes with artist Alex Impey’s recent show -gnostic cautery at The Hunterian Art Gallery in Glasgow, using as a starting point historical, abandoned practices where the marbling on sheep’s livers was interpreted to divine the future. Hendry’s film presents the body, each organ, as having different forms of sight and purposefulness attuned by their own distinctive consciousness or perceptions. I think too then this speaks about possessed bodies – supernatural possession and mediumship* as well as obsession and fixation. It speaks too of the body given over to or consumed by parasites, ventriloquism (literally to speak from the stomach) or the body assembled from different and conflicting parts pointing perhaps to Mary Shelly’s 1818 novel, Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. While the body vocalizing itself through means other than the voice and centered on the stomach as a ‘second brain’ reminds me of the work Crawl Space by Jane and Louise Wilson from 1995 which derives its distinctive body scarring message from the ‘help me’ scene in William Friedkin’s motion picture The Exorcist from 1973 with its narrative about the demonic possession of a young girl, of a fracture between science and faith and a notion of invasion, the body as porous – host and legion.

One of my lockdown goals has been to finish reading Hillel Schwartz vast 900 page publication on the history of sound Making Noise, From Babel to the Big Bang and one of its chapters entitled Stethoscopies of Stertor and Râle 1 chimes directly with Navel Gazing’s central motifs, those membranes between illness and wellness, normalcy and deviancy or disorder, of what external forces determine what is natural and unnatural and in turn to this moment of pandemic and a timely reminder of the body’s vitality and susceptibility. Schwartz’s writes on the subject of auscultation, the precursor to the modern stethoscope: “[French physician] Dr René Laennec listened-in upon the body, sounding off in its own, speaking out… in sounding the body, an ear to its interiority… he lent percussion to listen for repercussion” as “noises in the body are traditionally seen as signs of disorder” any reverberation would be an expression of illness. Schwartz goes onto to suggest that this audibility of the body lends itself to a parity with musical instruments saying that Laennec wrote “a mediate auscultation operated inside the sign of the flute, the instrument most closely associated with the human voice…” The suggestion here then is the body is an orchestra assembled from a variety of voices, and that wellness and illness could be deciphered across the body’s harmonious or disharmonious chorus, a notion picked up in the film soundscape from composer Joe Howe and extending to designers Neil McGuire and Fiona Hunter’s film credit mutating typeface.

If the gut’s rebellion can be thought of in terms of an illness her making peace with the rest of the body, reabsorbed back into the body’s equilibria could be considered an act of care and self-healing. Hendry’s film reminds us there is something sacred within the body’s myriad complexities.

- Making Noise, From Babel to the Big Bang , Zone Books, New York, 2011, P.202-222

I was not able to find an image online of Jane and Louise Wilson’s work but it can be found on page 23 of Gothic: Transmutations of Horror in Late 20th Century Art, ed. Christoph Grunenberg, ICA, MIT Press, Boston, 1997

*This reminds me of a conversation I had with Kirsty Hendry when the artist came to visit Stirling’s Smith Museum to inspect the bust of Helen Duncan, a medium who was the last person to be tried under the Witchcraft Act of 1735 or the Fraudulent Mediums Act, depending on which source you reference and who was known to produce ectoplasm during seances, though from documentary evidence this was most likely to be cheesecloth regurgitated from Duncan’s stomach.

Hippocrates said “all disease begins in the gut”

Still from Kirsty Hendry, Navel Gazing, 2020 courtesy of Collective and the artist.

Collective

City Observatory

38 Calton Hill

Edinburgh

EH7 5AA

I am no longer writing for publication’s like A-N, Aesthetica or This is Tomorrow as they don’t pay writers, which benefits these publications enormously and the galleries too, but might not serve the artist or writer very well. This is unsustainable. I am happy to write pro bono where I see a professional developmental benefit for my own practice in film, as is evident here. I am also thinking about having a separate website to host my writing, and would welcome comments or feedback on this.