LUX Scotland Artists’ Moving Image Festival at Tramway

A2 colour edition of commissioned writing, November 2016

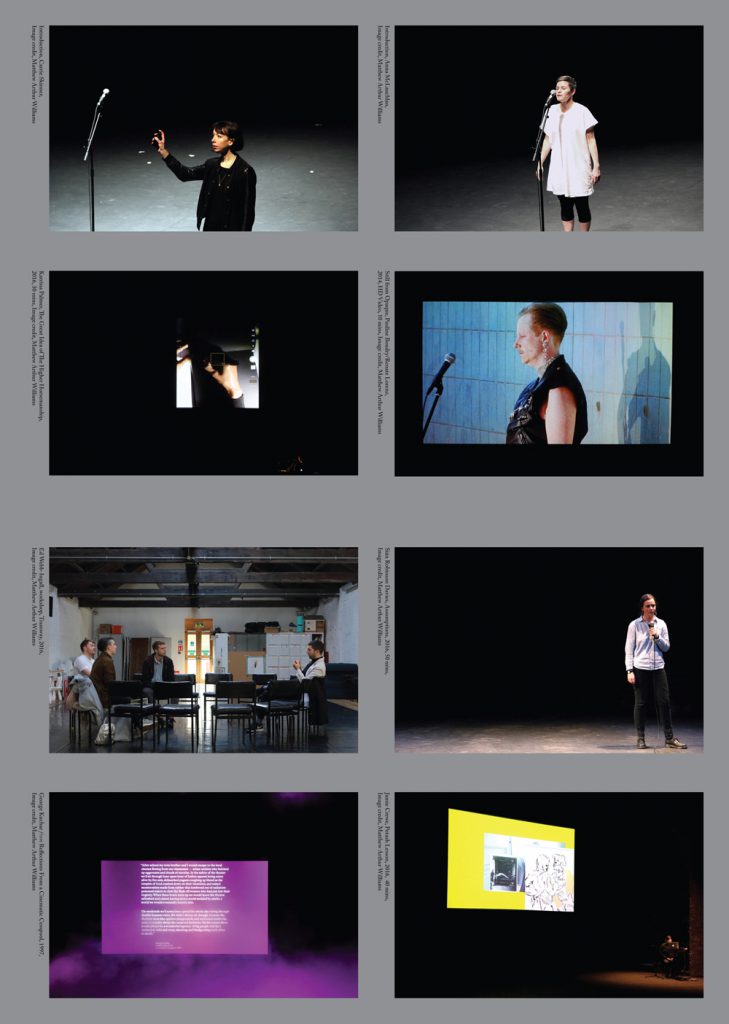

A commissioned report on the two-day Festival of screenings and performances programmed by Sarah Tripp and Ed Webb-Ingall. Works include pieces by artists Katrina Palmer, Sarah Forrest, Jamie Crewe, Sian Robison Davies, Jérôme Bel, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Lucy Lippard & Cinenova among others.

Extract from Day One, Sarah Tripp’s ‘Making People Up’

A graceful prologue to artist Sarah Tripp’s project in three acts Making People Up for the first day of the Artists Moving Image Festival sets out a series of gestures and shapes that represent an abstract of the entirety of actions about to unfold. The phrase ‘Ich bin Susanne Linke’ is spoken three times by different people, while a dance disguised behind a length of black fabric is made all the more mysterious by a performer spraying perfume into the audience using her jacket to waft its mists across the hall. Sensations other than sight and hearing are alerted; this then is an environment where moving image is primed to be experienced in physical or subconscious ways. Coincidences, serendipity, ‘in moments of good fortune, on lovely evenings’, folds of time and space and even psychic phenomenon are alluded to in these opening passages.

Tripp’s programme, conscious of its theatrical place and positioning, sets out film and moving image superimposed with performance. Characters with mutable identities appear and disappear and whose properties and qualities, on screen and in physical presences, are held within veils, masks, breaths, curtains, choreographed repetitious gestures, imitations, cover versions, smoke and perfume. Meanwhile the voice is often separated from the screen and heard from off-stage or lip-synched from elsewhere, pitch-shifted and incongruent. Much is made of the workings of stage management: setting up equipment, striking the set, moving microphones and positioning spotlights and the illumination or dimming of this black-box theatre space’s house lights. Many works are co-opted into play to feature within Tripp’s broader speculations on the restless screen. The act of reading and collaging references from literature are evident throughout. While only in hindsight, once the closing passages of artist Jamie Crewe’s spoken word performance high on the vapours of Amyl Nitrite begin to ‘come down’ at the end of the Festival, can one see the chance encounters and echoes and overlays played across these two days. And among many is a description from 1848 of acrobat Susannah Darby suspended in mid-air on horse back during a circus act that would lead to her death and the centrifugal forces that come to define circus’ round-house architecture with a manipulated photograph of an unknown baseball player suspended in mid-air, in flight over the field’s triangle, about to reach ‘home’.

Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz, film Opaque, 2014 and Jérôme Bel, The Last Performance, 1998 play out in the first act, a rhyming couplet of works on performing and its contradictions or paradoxes, on impossible positions from which to be defined, behind veils and smokescreens, of being one thing and not another or simultaneously being many things. Each character in French choreographer Bel’s work is and is not at various stages himself, Hamlet, Calvin Klein, André Agassi and veteran German dancer and choreographer Susanne Linke. Bel’s video of a performance in repetition is the source of the prologue’s phrase ‘Ich bin Susanne Linke’, as well as the source of its mysterious perfume act and disguised dance piece. Tripp’s folds our memories back to ourselves, time is also incongruent, chronologies becomes inconsistent, actions disentangle themselves from the screen – and the past – and becomes dimensional.

Katrina Palmer’s, The Great Idea of the Higher Horsemanship, 2016 is an exquisite opening to act two and is beautifully played throughout. A combined spoken word analysis, visual demonstration and personal poetic essay that takes at its root the grave of acrobat Susannah Darby sited in the grounds of the art school in Leeds, the narrative that led to her death in 1848 and her husband Pablo Fanque’s Fair – Britain’s first black circus owner, and a possible supernatural clairaudient encounter in the art school’s silent reading room with Darby’s incorporeal voice: ‘Can you hear me?’ they both announce. Palmer introduces a further text The Chronic Argonauts, a short story by HG Wells published in 1888 that relates through different narrators a series of encounters with Dr Moses Nebogipfel, a time traveller, an anachronic man seeking a place in time more suited to his vision and abilities. Palmer uses this literary time-machine device and a momentary Droste effect or mise-en-abyme image to set up a series of situations where the acrobat Darby might be forever suspended in time with multiple, failed, attempts made to save her by catching her at the moment before she falls.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Vapour, 2015, a black-and-white and silent film starts at the moment where Palmer’s voice closes on Susannah’s ‘lovely evening’. The Thai director and filmmaker’s work sees an unexplained smoke emerge from a rural homestead and slowly engulf the activities, neutral at first and then increasingly nefarious, of its surrounding inhabitants. Shot in Toongha village in the Mae Ram district of Thailand the film is a ‘psychic battleground’ between the state and its claims to territorial rights and resources and the country’s population. The smoke in Weerasethakul’s film is as sinister and unknowable as the preserved whale from a travelling circus sideshow that inspires social chaos in Hungarian director Béla Tarr’s motion picture Werckmeister Harmonies from 2000.

Sarah Forrest’s In one moment she wrote me as headless, 2016, is a performance and HD video that plays across an increasing agitated drumbeat, rock-and-roll music sample and a textual narrative about a fissure leading to another dimension opening up in a domestic space. Texts on screen synchronise with the drumbeat while they appear to be erased by sequences of video of wafting curtains. Fiction, sound, narration, character and meaning pulse in and out of focus destabilising our sense of certainty, its whereabouts sitting out of time.

This hesitancy of encounter, who someone is or might pretend or become to be is a device which is then picked up by Rotterdam-based British artist Kate Brigg’s Thinner, thicker, mixeder, smoother, 2016, a spoken-word performance where characters described in fiction flow in and out of focus with a self-conscious scrutiny of herself and her position to us, the audience. She self-portrays as just another ‘minor’ character that she describes as a ‘roving gas’ alongside the multitude of characters we have met, thought about, dreamt about, forgotten about in film, fiction, news stories and through real life.

The final act of Tripp’s theatrical triumvirate screens the impossibly beautiful 16mm film by London-based artist Holly Antrum, Catalogue, 2012-2104. In it Antrum conducts a kind of visual interview exchanging perspectives – through masks, veils of gold foil and a circle of semi-transparent corrugated plastic – with the nonagenarian artist, performer and poet Jennifer Pike. The camera passes over objects, materials and surfaces in Pike’s home. Later the camera rests on drawings, assemblages and paintings at an exhibition at Camden Arts Centre, while her recitation of concrete poetry such as ABC of Sound, 1964, by her late husband and collaborator Bob Cobbing, are described as a ‘word-surfaces and obstructions’. Antrum’s film stages through its composition in 16mm film language as sculpture, and Pike’s voice, edited in the digital and unsteady in places, as instrument and material, just as Kate Briggs’ prior performance described words ‘in terms of noise as a substance.’

The closing episode sees Edinburgh-based artist Siân Robinson Davies, Assumptions, 2016, conduct an experimental performance in live improvisation and stand-up comedy. A member of the audience is recruited to perform with Davies a series of assumptions about each other, based on a premise that they would have never met prior to this encounter and drawing on imagined or the visual clues they present through apparencies of age, clothing, gender, nationality – evidence of the processes, however inaccurate and prejudicial, in Making People Up.