‘Talking, counting, blinking, noting’ 16mm film as a collaborative action

Titles

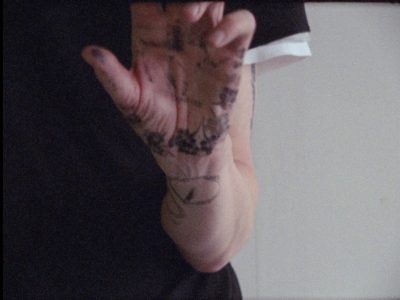

Anonymous Writes A Spell for the Camera/Michelle Hannah’s Arm/Marisa’s High, with Michelle Hannah, 2019

An imaginative substitution/Burdens, with Emma Balkind, 2019

The Right of the Majority to Rule, with Rowan Markson, 2019

Atmospheric phenomenon are expressions of universal sympathy, with Leah Millar, 2019

The Name which is not yours, with Rosie Roberts, 2019

Provisional titles Bouquets 1 and 2, with Wendy Kirkup, 2019/2020 (from a series of paintings by Willem van Aelst, Jan Davids, Rachel Ruysch (rejected attribution) and Jacob Marrel)

The voice is a stem, with Helen McCrorie, 2019

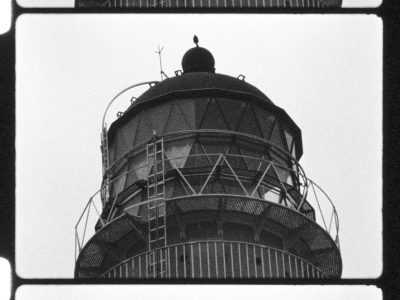

The Window; Time Passes; To the Lighthouse, with Nathalie de Briey, 2019/2020

A Spell for Surrounding, with Anonymous, 2019

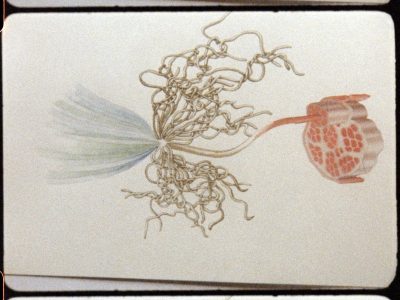

The Book of Sleep/Mysterious bulbs and botched isms, with Catherine Street, 2019

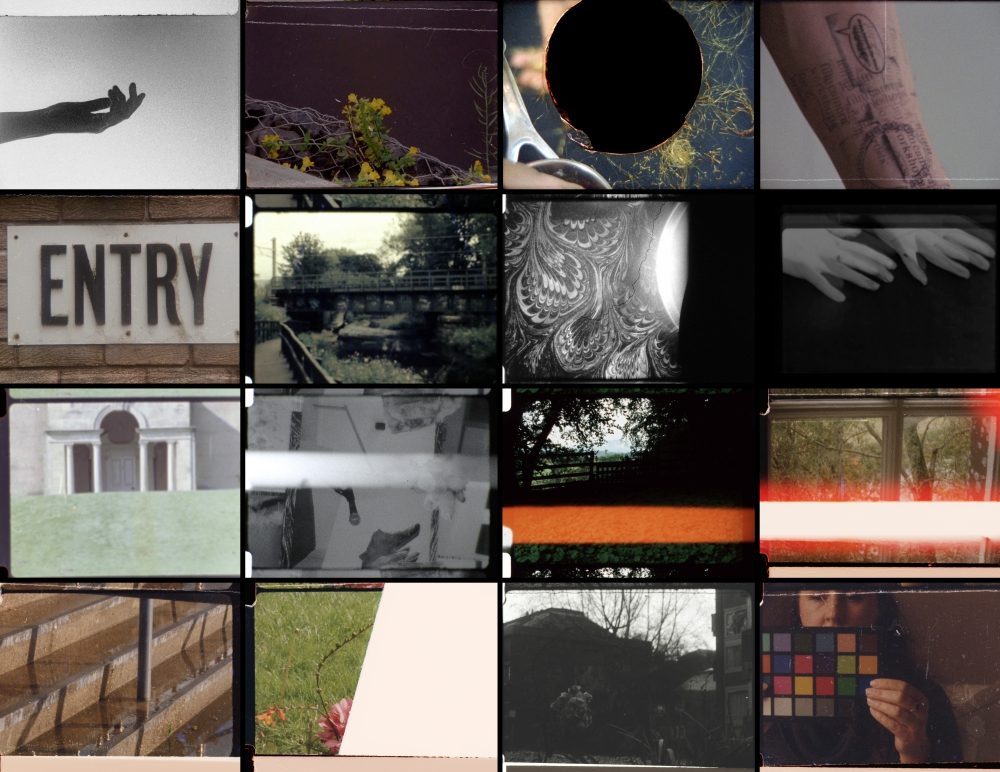

Featured collage of end frames, 16mm, 2019-2020

Film Stills

“The experience of the unseen listener”§

Among titles. Trespassing and invitations. Smoke and tension. An essay structure without names. “I wear all the colors of the house.” A Restoring Slowness.

If done correctly working collaboratively might allow you to disappear, for a moment, and could therefore be thought of as a magical act.

All things must have more than one title or name, while some processes allow something to name itself. Talking. When you speak to this thing you speak to all of its ancestors.

What does it mean to record and adopt the biographies and subjects of another and, taking the form of collaborative actions, translate these experiences to film? What does it mean to act collectively or as an assembly around the subject of collaboration, which is also meant to be left out of sight? Counting.

This film, or filmic materials in the form of glimpsed passages and recordings, in found-through-trust, plural image-making, is constructed as an attempt to conjoin the edges, of connecting margins, of stitching together holes and gaps. While adding to this incertitude, full of doubt, the film work is presented out of sequence. It is evidence of a deliberately unfinished and limited narrative made from encounters between artists, time, cameras, subjects, materials and references with many things held back, or omitted, and which often loop back in attempts to consider things like likeness and difference, betweenness, interstices, something unfixed, the immanent, blindness, trust, disappearance, finding the name for something. Fragmented messages and dispersal. Blinking. It is a film about about delay, an archive of imprecise purpose, a library of perforations. Much of the film takes place through gestures of the hand, which forms part of our visual, bodily storytelling, or takes place at sites which speak about personal meaning, tied in with ideas of care and memory. Often things are impressed upon the body and make announcements about biography, place, now and memory. Clearly all of this plays out like a dream, full of paradoxes, agitated and delicate, precise personal revelations and blurriness, smoke and tension. Images are slight, concealed, disguised and protected, plotted out by informal meetings (over the operative mechanisms of clockwork and electrical film cameras). I am reminded that my motivation for this work is to produce something deliberately rich because I want you to know what austerity means. Noting.

Counting. I am thinking about this film as a space, or nearby a space, and that in different circumstances it would have been an exhibition, as it is it is scattered and disjointed and measures time through its gaps and a hesitation for closure. As the narrator, Sylvie, in Chris Kraus’s novel ‘Torpor”, 2017 ruminates:

‘To organize events sequentially is to take away their power. Better to hold on to memories in fragments, better to stop and circle back each time you feel the lump rise in your throat.’

“My behavior on this shoot has been irritable and unreliable, peaceful and gentle, awkward and intimidated, energetic and blessed, frightened and relieved, grateful and excitable, distracted and mournful, angry and high.”

Robert Ashley, speaking in Part 3, ‘Questions and Answers’ from his opera ‘Now Eleanor’s Idea’, 1994-95 asks: “Is it possible to find a part of yourself that you did not know was lost? Is it possible to discover that you are someone other than who you think you are?” I said this during the performance of ‘Twin Eye’*, and also said: ‘the spaces of appearance are complex, and how you might exist, and sustain a livable life, in those spaces might not yet be legible. Collaboration, as a process to engage with might make that something, to be able to name oneself in the interstices of naming, become legible.’

I think collaboration allows me to disappear for a period of time.

Talking. During a conversation about collaboration with the moving image artist Anne-Marie Copestake she tells me she thinks there is no singular definition of collaboration other than it exists in a grey area, responsive to the circumstances the collaborators are bringing to or come seeking from the work, but is nevertheless something that needs to be protected. This idea of protection then really chimes with me. To my mind then collaboration is not a core, or an aim, it is rather a method for surrounding.

So that might be a dream or the conduct of a sleepwalker or absent mindedness, or fortune telling or concocting spells.

§ ‘How to Disappear’, Haytham El-Wardany, Sternberg Press, NYC, January 2020

1. ‘Tonight the World’, Daria Martin’, Barbican, London, Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco, 2018, quoted in the essay ‘The ‘Paradoxical Gift’ of Another Woman’s Dreams’ by Maria Walsh, Chris Kraus reference comes from page 12.

• Cooper Gallery, DJCAD, Wednesday 18th September 2019, 5-8.00pm

“Am I that name?” And sometimes we keep on asking it until we make a decision that we are or are not that name, or we try to find a better name for the life we wish to live, or we endeavor to live in the interstices among all the names.” Judith Butler, Page 61. Gender Politics and the Right to Appear, Notes toward a performative theory of assembly, Harvard, 2018

*

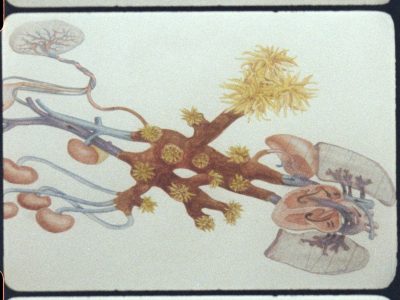

“Still life with flowers in a glass vase on a stone leaf. Bouquet with a day flower, rose (white, pink), wheat, cow parsley, carnation (red-white), trosnarcis, or Narcissus, sleeping bulb, tulip (red-white), sweet pea, dog rose, honeysuckle, lapflower, Gelderland rose, anemone (red) and an anemone on the plinth (red); furthermore an Atlanta butterfly, a caterpillar or psi butterfly, a span caterpillar, beetles, ants and other insects, spiders and a garden snail.”

‘I do not intend to speak about. Just speak near-by’

from ‘Reassemblage’, Trinh T. Minh-ha, (Video, Vietnam, 1980)

Every part of this film is given a name, that might suggest some of the experiences while discussing the project or the things encountered during the shoot. That title, just like the voice that will be speaking these words, will change depending on how the material is edited and presented. The title often attaches the film, and its images, to the written word. Talking.

Spectra.

This is a silent film and is monoecious, the film changes sex, with a male body and female parts, flowers and branches. Its gender vanishes into the body, arms and eyes of the other. *

Noting. In the pursuit of a masked image showing two still lives at the same time, and on the visual lists given by Dutch painters to accompany, descriptively their works, we discovered these flowers could never appear simultaneously, they don’t bloom in nature at the same time. I think these images then are about showing off their construction, over many months, rather than the moment you are meant to believe that they exist in, and speak of an incredible financial and time wealth that would allow someone to collect them and display them and have them recorded in this way. These images are full of time gaps and slips, and pauses and waiting, these holes are mostly all invisible. What can be often seen, emerging from an almost universally black background, is one thing that turns into another. Dust, which is skin that has turned into debris, shells, butterflies. Counting.

These diaristic lists, time and materials descriptive lists are words that replace images, and in a way return the work to a kind of blindness, writing and feeling and thinking around the image. Wendy talks to me about time doubling as well as hope, lenses, glass, transparencies, opacities, navigators, and masking as though these things were the same thing. And some of her thoughts on lenses and glass and light (Blinking. On and off.) are entirely identical to things that Nathalie talks about when she talks about lighthouses.

How do you paint dust?

*I read this description of the Fortingall Yew, situated in Perthshire and Scotland’s oldest tree: ‘The yew is male, however in 2015 scientists from the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh reported that one small branch on the outer part of the crown had changed sex and begun to bear a small group of berries’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fortingall_Yew, retrieved 26 December 2019)

*

“Finally she spoke. “Do you love me, John?” she asked. “You know I love you, darling,” he replied. “I love you more than tongue can tell. You are the light of my life, my sun, moon and stars. You are my everything. Without you I have no reason for being.”

Again there was silence as the two lovers sat on a park bench, their bodies touching, holding hands in the moonlight. Once more she spoke. “How much do you love me, John?” she asked. He answered: “How much do I love you? Count the stars in the sky. Measure the waters of the oceans with a teaspoon. Number the grains of sand on the sea shore. Impossible, you say.”*

I am fascinated by Emma making her own clothes and the simplicity and honesty of these garments. I thought about the parity of filmmaking and dressmaking, about piecing together things from a pattern to be worn and made visible on the body. Emma’s film, which was shot at different locations at the housing estate in the south side of Glasgow, in an apartment that she shares with her husband Joe, although those interior spaces don’t make it to the film, is about love.

‘At the heart of the Cinématographe was the film transport mechanism, whereby two pins or ‘claws’ were inserted into sprocket holes at each side of the film, moved it down and were then retracted, leaving the film stationary for exposure. This intermittent movement was designed by Louis and based on the principle of the sewing machine mechanism.’§

It is also about losses and one roll of film went missing in the post and some of the first roll of film has a light leak or a loose fitting filter managed to obscure some of the images we were shooting. We shot at the height of the heat and light of summer and again, on a shot-by-shot reshoot, assisted by filmmaker Lydia Beilby, on the coldest day in December and where summer events met us again as winter artifacts including a strange hybrid flower, seen in final frames, where one flower has managed to grow through another, creating a vivid amalgamation. Of course Emma doesn’t know this but the film is a bouquet of flowers for her and Joe (but I hope she recognizes this when she comes to read it and see the film) and has references throughout to 16mm films (and cut by glimpses, looking at memory and remembered moments in short bursts, (Blinking)) by Margaret Tait (‘Garden Pieces’, 1998 especially the close ups of Tait’s poppies), Ute Aurand (‘Maria und die Welt’ 1995), Luke Fowler (‘Paddington Collaboration’, 2009), Rose Lowder (‘Les Tournesols’, 1982), Marie Menken (‘Glimpse of the Garden’, 1957), Caryn Cline (‘Lucy’s Terrace’, 2009) and Rudy Burckhardt (‘Summer’ 1970).

I have not seen the two time-mirror films yet (I am still writing this while film processing is on hold, over the holidays, at the laboratory) and I am wondering how much they will match and align and fall into synchronicity or when the images and timings start to go astray. Or if there will be another loss. Blinking. There’s a single magpie in the first shoot, one for sorrow, and when on the second shoot, with no bird around, Lydia used her hands to recreate a bird shape that referenced the clenching hands with splayed fingers from Laida Lertxundi’s 16mm film ‘WORDS, PLANETS’, 2018.**

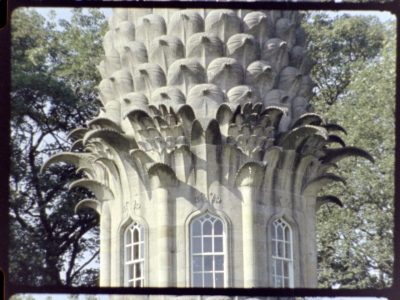

“She deserves the order of the square halo, first class, with harps in diamonds”, remarked artist Dwight Ripley on Menken’s film, whose strange drawings, made of hybrids and enfolding sculptural patterns, were among things I also began to look at when making Emma’s film. These drawings include ‘Evolution with Mushrooms, Bud, and Pineapple’, from 1946 and ‘Constellations in a Cage’ from 1951.

*Text from Samuel M. Johnson, ‘Knee Play 5’, Philip Glass/Robert Wilson, from ‘Einstein on the Beach’, 1976

§On Auguste and Louis Lumière: https://blog.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/the-lumiere-brothers-pioneers-of-cinema-and-colour-photography/ (retrieved 01 January 2020)

**’WORDS, PLANETS’, http://laidalertxundi.com/WordsPlanets.html (retrieved 31 December 2019)

*

I have come to trust myself better on this film.

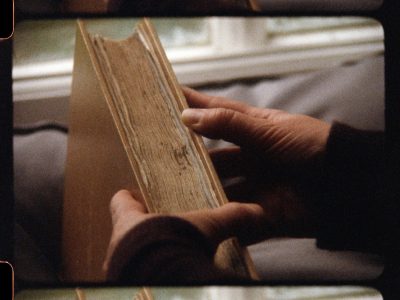

The voice is a stem. (The page is a stem.) Counting. At Crieff, we are traveling to Innerpeffray Library, Scotland’s oldest lending library and now a museum of a library, where the Keeper tells me, back when it was in use, that its circumference of readers, borrowers could be depicted by a 15 mile circle. The building – a white villa on two floors almost adjoined, we measured this distance, it is mere inches, to St Mary’s chapel, a long, tall church hall that also acted as a school building until 1947 – sits in in the middle of a cemetery. The chapel houses the extraordinary Faichney memorial, a naively carved form manufactured from immeasurable pain and grief. It was carved by John Faichney, a mason, and whose name appears in the Library’s Borrower’s Register, commemorates his wife Joanna, who died in 1707 and no fewer than ten of their children who had predeceased her. The couple are carved on the head of the stone, while the columns on either side of the body of the stone display small figures depicting each child. The memorial doesn’t appear in the film (the chapel where it resides was too dark for the roll of 16mm film I had) though I took stills of it on a 250D 35mm motion picture stock which was eventually processed in the wrong chemistry at the laboratory and the resulting roll is full of image ‘noise’. Blinking. I think about something so troubling you have to close your eyes, even for a moment. Deliberate blindness. I think of some of the artifacts on these images might be some kind of transmitted grief; leaving the library, which is very remote, and as we drive down the single track road to rejoin the main highway to return home my mouth erupts in terrible toothache.*

*Things we note on this shoot include reading the Borrower’s Register and trying to find the names of women (and their occupation) among the list of names and titles of books lent out, also the marks made to erase names in the register… poisonous vegetation like Yew trees and mushrooms and superstition and spirits associated with Rowan trees (their berries are symbolic of droplets of blood… “a Scottish superstition warns that it’s bad luck to cut down a Rowan Tree. Its wood was traditionally employed in the fabrication of walking sticks, coffins, crosses and wizards’ wands… The trees are associated with prophecy and creativity” and “The perseverance associated with the yew is that of all life, which continues in the face of overwhelming odds and grows stronger because of it. Much of the yew’s symbolism is concerned with transcendence, the transformation that arises from death… and that yew trees are in contact with the dead… and that yew trees are symbolic of protection…”

*

In ‘The Book of Sleep’*, by Haytham El-Wardany, the Egyptian writer talks about sleep as “a Shared Absence”, saying of the “In this absence, the self returns to itself, and to attain this goal it must fall. The fall into sleep… causes the self to lose control and drop deep into itself. The further it falls and the deeper it sinks, the closer it comes to itself. Its journey of descent continues and return is only accomplished when it ceases to be aware of any distinction between what is it and what is not.”

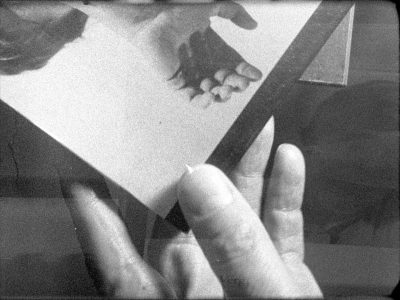

Sleep comes with a sense of blindness and the presence of another kind of ‘sight’ of envisioning impossible scenarios and enfolding memory, fantasy, desire, anxiety and fictions, consolidating memories to long term… dreams. I think about the blind actions in film, loading and unloading a camera in the dark and shooting blind, removing the eye from the viewfinder, I think about the camera as a sleeping device, and about my absence in its presence. Catherine’s artwork on paper, collages and water colors of bodily elements, mineral matter, plant and oceanic anatomies make new hybrid bodies possible. Spilling muscle, levitating coral and water hearts and paper ventricles. More things that cannot in nature exist together. Blinking.

What narratives do you abandon, that you did not know you abandoned, when you fell asleep and when you awoke? How do you film someone asleep or ask someone to be blind or be asleep on film? We talk about stage directions, where the director asks the actor to walk forward but act, in her mind, as though she is walking backwards. I wanted that tension to be sensed (not seen) on film. I asked Catherine who is an artist interested in the body (performing its materials) and its presence, to be absent and in a way to disappear. These non-actions are punctuated with images, works on paper, that might as well be dreams.

These ideas of sight and seeing and blindness brings to mind the 35mm film ‘This Quality’, 2010, by filmmaker artist Rosalind Nashashibi that was “shot in downtown Cairo and comprises of two halves: the first shows a 30-something woman looking directly at the camera, and sometimes acknowledging the existence of others around her who we cannot see. She has a beautiful face with eyes which seem to see internally rather than outwardly, they almost have the appearance of being painted on, suggesting the blindness of a mythological seer.” (This description from LUX’s Collection page.)

This brings to my mind an idea about Tiresias, a blind seer from Greek mythology who is presented as a complexly liminal figure and whose narrative sees him transformed into a woman for seven years, mediating between humankind and the gods, male and female, blind and seeing, present and future… and whose clairvoyance presented itself through images ‘seen’ in smoke, fire, water, made through interpreting the behavior of animals, and communications with those asleep and with those who have passed on. Talking.

‘Surplus hours of no benefit or purpose; and yet these hours do not wither and fade away like pointless superfluity but grow in number, night after night, to become a strange assemblage.’*

‘And I know what I know and I know that orchids seduce.’

*’Fragments from ‘The Book of Sleep”, Haytham el-Wardany, https://luleabiennial.se/en/journalen/nr-4/fragments-from-the-book-of-sleep (retrieved 02 January 2020)

“I gather up the person I am over an accumulation of 53 years asleep. Counting. A man who lives in an unconscious world that you will never know.”

*

A current of air, wind, breath, the vital principle.

What is revitalized through the action of a sigh? How could we be absent together?

*

‘The homes are eternally wounded, covering up their lesions with ever more drapes and veils. A man passes his whole life within them concealed behind walls, until, one day, a distant sound comes to his ears, a sound that flows through all these obstacles, overleaps and is channeled through them. How did this sound make it in here?’**

‘Photograph the dust falling on the city, on the windows, on the books, everywhere’, Jonas Mekas, film frame, ‘On Luigi Porto’ from ‘Mekas’ Diaries, Notes and Sketches’, 16mm film, 1969

Time has reminded me that Rosie’s film was shaped by a walk in the south side of Glasgow where we discuss things about care, distraction, trust, the plural, childhood, medals and moving, changing and settling. Her film is about ecstasy and panic too. About football. Rituals, and hot bodies, drama and perseverance. And to my mind is somewhat haunted in places. I think a lot about the late Belgian painter Raoul De Keyser when we are talking but for most of the time when we are moving around, because I am distracted, (there was a man I loved who lives in the vicinity), I cannot remember his name. In the film there are empty spaces and figures appearing in the distance, gestures of the hand, tension and the sensory, and a sense of movement about to happen, spectatorship and sport. It is an elusive narrative. But brought back to solid ground through thoughts about film when a flock of magpies appear. Counting.

One for sorrow, Two for joy, Three for a girl, Four for a boy, Five for silver,

Six for gold, Seven for a secret, Never to be told. Eight for a wish, Nine for a kiss, Ten for a bird, You must not miss.

The film looks at the sky and then to the markings on a football pitch and walks out the center circle’s circumference. Counting. And we talk about Tacita Dean’s ‘Pie’, 16mm film, 2003, described as ‘[Dean] records the view through her studio window of magpies flocking in the birch trees outside, giving a more intimate reading of the presence of nature and the process of artistic activity from within the city.’

I think about making sense of time passing, how the nursery rhyme gives an interpretive meaning to the meaninglessness of a flocking of birds.

(Somewhere in my mind I am reminded that when filming this work the temperature range between outside and inside (extremes of heat and cold) affected the film as it was transported through the gate and that when the film print is projected it reveals this distortion through a kind warp of time, the shiver, or breathing of the celluloid.)

Tacita Dean tells the writer Marina Warner: “All the things I am attracted to are just about to disappear…” *

Rosie reminds me that you cannot remain unaffected by the environmental conditions that appear around you.

**‘How to Disappear’, Haytham El-Wardany, Sternberg Press, NYC, January 2020

*’The Changing Light at Craneway, On the film projects of Tacita Dean, everything is just about to disappear’, Barry Schwabsky, The Nation, July 2010 Issue, https://www.thenation.com/article/changing-light-craneway/ (retrieved 31 December 2019)

*

Blinking. To the lighthouse. The Window. Time passing.

“What accounts for the constant and imperceptible opening and closing of the human eye? Each of the hundreds of daily blinks in fact function as a form of cognitive release. They disengage attention by momentarily deactivating the dorsal attention network that allocates focus to locations, objects and features. Cortical activity during these blinks include the regions of the brain associated with introspection. The blink is not merely a black frame inserted into the pulsing film of experience… each blink is like an instant daydream and a second look. There are various ways to test the rate and reflex of these passing daydreams and double takes…” *

‘The principle of hope’. Whose eyes see that beam of light?

“Antagonism is an electrical field.“

Nathalie’s film, about joining with the unknown, a work with a serendipitous backstory, is composed, like a prism, through an array of references, positions, sounds, images and reflections. It is suggestive of cyclical or repetitious phenomenon, in particular the phases of the moon, sunrises and sunsets, and observed holidays, and takes form whispering out the possibilities, and meanings encountered, through the projected revolving beam transmitting from a lighthouse. The film, in flashes of light, retraces and recounts some of these moments. Moments which are also a vital to a series of flip books made over the course of Nathalie’s career, taking crucial frames from passages in cinema works like ‘400 Blows’, 1959, by François Truffaut and ‘The loneliness of the long distance runner’, 1962 directed by Tony Richardson, as well as a series of books describing the sunrise: “each captures a different moment of the sunrise taken between 5.45 to 6.15am on 31st May 2001; the sunrise starting with its green and orange glow, the seagulls at rest on the roof taking to flight at different moments of the sunrise. Looking towards Antarctica from this harbour we can only imagine what the destination is like and what the journey could be; something we cannot see directly but we know it is there. Looking beyond the horizon.”**

Passages of film and documentation enfold within each other and scenes from loading film and stills from field notes finds its way into footage, by day, at Barns Ness lighthouse by Dunbar and by night at St Abb’s lighthouse, both on the East Lothian coastline. St Abb’s is set on a rock shelf overlooking the sea and projects from below eye level not above, a revolution of 12-15 seconds, while Barns Ness now no longer operates, and is therefore blind, being decommissioned in 2005. Blinking.

We are reminded that Tacita Dean’s ‘Disappearance at Sea’, 1996, a 16mm colour film with sound was shot on location at the lighthouse on St. Abb’s Head in Berwick-upon-Tweed in northern England, while our film is shot at the lighthouse at St. Abb’s in Berwickshire. “The film was inspired by the story of Donald Crowhurst (1932–1969), a British businessman and amateur sailor who died while attempting a voyage around the world during which he falsified his progress.” In 1997 Dean explained how she has interpreted Crowhurst’s expedition:

“His story is about human failing; about pitching his sanity against the sea; where there is no human presence or support system left on which to hang a tortured psychological state. His was a world of acute solitude, filled with the ramblings of a troubled mind””***

A second film used as a reference is ‘Flash in the Metropolitan’, 2006, by Nashashibi/Skaer, another encounter with objects, their extended histories and ideas finding illumination in the brightest and briefest of moments: “These ancient objects are granted only a split second in the limelight, lit up by a flashing strobe, but the metronomic regularity of those flashes reverses the transitory nature of these brief glimpses…”

At St Abb’s lighthouse last night and the light it was projecting affected my camera making the engine speed up! This is the third camera ‘incident’ on the shoot, including the ‘concertina’ of film misloaded onto the take-up spool, the battery draining at Dunbar, along this coast something can be sensed in the air that these can cameras ‘detect’. Nathalie and I could both feel this too, a weight, an exhilaration, hearts racing, a presence. Ghosts. Blinking.

‘To the Lighthouse‘, Virginia Woolf, 1927, but backwards.

*‘Figuring, Counting, Blinking, Noting’, João Ribas, from João Maria Gusmao and Pedro Paiva, ‘The Sleeping Hippopotamus and the Missing Eskimo’, 2016, Aargauer Kunsthaus, Kolnischer Kunstverein, page 97.

**’The Edge of the World‘, 2004, http://www.nathaliedebriey.com/Site/PROJECTS_THE_EDGE.html (retrieved 02 January 2020)

***‘Disappearance at Sea’, Tacita Dean, 16mm film with sound, colour, 1996, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/dean-disappearance-at-sea-t07455 (retrieved 02 January 2019)

*

It fell to Miss Jourdain to explain colour prejudice to me.

The home of gesture.

Ivan spent many hours making spun-sugar centre-pieces like galleons or temples which he filled with sweets and fruits he himself had glazed. He used to send a miniature version of the great set pieces up to my day nursery for me.

We felt that time was running out, that another war would involve the whole of Europe believing that the civilization we loved was under threat, we lived in the present, setting great store on friendship and art. Since artistry expressed all that is best in human nature, we sought it in the contemporary arts, in haute cuisine, in the remains of ancient civilisations and the beauties of nature.

While sipping his yoghurt David glanced at a boulder that must have rolled down the mountain to rest inconveniently close to our host’s door.

“Why don’t you move that stone?’, David asked.

Our elderly host slapped his leg and petulantly retorted: “you have not even been here an hour and you are already considering changes; after three years here it has never occurred to any of us to change anything.

The spell was broken…

It was difficult for us, passports safely to hand to understand the despair of suddenly finding oneself stateless, with no right to abode, no freedom of movement, no permission to make a living. Tamara used to often say that on leaving Russia her mother impressed on her that she would a guest wherever she lived, with a guest’s obligations, or courtesy of compliance and of restraint from criticism.

If foredoomed, was it quixotic to try and live according to one’s principles, should fortitude rather than hope be one’s aim? All too often I concluded that it would be wisest to enjoy life when the going was good.

A lump of wax on a shovel was held over a fire until it melted when it had to be tipped very rapidly into the near-freezing water, as it solidified the wax formed into shapes which were regarded as omens. Oddly enough year after year mine was solidified into a galleon or boat – a symbol of travel.

*

The home of gesture. We wish to dedicate this sequence to the artist and curator Paul Moss (25 February 1975 – 14 February 2019), and his wife, the artist Cecilia Stenbom, while the title: “Atmospheric phenomena are expressions of universal sympathy…” comes from an essay ‘Shamanic Cinema’ by Philippe-Alain Michaud on the ‘poetical philosophical fictions’ of the work of artists João Maria Gusmão & Pedro Paiva in the exhibition catalog ‘Celluloid’*

This encounter surrounds portraiture developed through physical gestures, skin, peculiarities of movement peculiar to a person, and about grace, about edges and margins and boundaries and is articulated through drawing, painting, the effects of salts, chalk and stains on emulsion, the kinds of actions on film for the agitation and excitable atoms of projected cameraless film loops and in turn to marks made on the body, with deliberation and also absent-mindedly, about the body’s properties, surfaces, vulnerabilities and equally the hand’s sensitivities. Noting. I think the film is about actions to purify, the river, as an action, is never far from the frame and something of a seance to acknowledge passing and absence and what and who has been lost. A filmic addendum to the portrait films was an experiment with masking and double exposures, around the river at Newcastle and Gateshead, overlaid and multiplied over the water that flows through Stirling. While both rolls of film document interruptions in the form of a fire alarm when were shooting at the Newbridge project, and then later a power cut at the house that Leah was looking after while the occupants took a long vacation around Europe following a death of a beloved friend, artist and father.

*Page 52, EYE Museum, Amsterdam, 17 September 2016 through 8 January 2017, with written contributions from the artists, and essays by Cristina Cámara Bello, John Hanhardt, Marc Glöde, Jaap Guldemond, Philippe-Alain Michaud and Mark Nash. https://www.eyefilm.nl/en/exhibition/celluloid (retrieved 03 January 2020)

The material I have come to understand. The work is made to consider disappearance. Film as a kind of glossolalia of spell-making, excavating time, togetherness and psychic possibilities. Using placeholders and substitutions to mark out things which could not make it to the frame. How could something not be filmed? Elusive images and narratives. I understand that I am an inadequate artist, without a companion, I am half and incomplete*, and these images record something missing and absent that has been present all of my life.

It is composed of likeness and difference, and transmissions and shared states of consciousness, burdens, restoration, ghosts, reclusiveness, care, democracy, consuming, romance, atmospheres, marking and a refusal for coherent order. It is about the immanent and external, the willed and unwilled, the excitable, finding a title, and a vocabulary, in the interstices among all the names.

What we take on and what we arrive at.

*“how… do you add something that is also a subtraction, construct the irreducible, disappear and don’t… [and remain] forever incomplete?”, Martin Herbert,’Tell Them I Said No‘, Sternberg Press, Berlin, Page 92, on Christopher D’Arcangelo

A note on the origin of Marisa’s High: “He found a way to walk past me, giving instructions to the crew – ‘Let’s move on to 32, move those lights into the foreground’ and so on – but as he passed me, he grabbed my hand and squeezed it. It was the most beautiful and appreciated gesture in my life. It was the greatest moment in my career.”

Stanley Kubrick’s ‘Barry Lyndon‘ (1975) : ‘It puts a spell on people’ Marisa Berenson: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/jul/14/stanley-kubrick-barry-lyndon-put-spell-on-people (retrieved 16 January 2020)

Published 02 January 2020, with further edits to come.

Placeholder for Wendy Kirkup text.

Supported by an Open Project award from Creative Scotland and Made possible with the financial assistance of Visual Artists and Craft Maker Awards: Forth Valley & West Lothian. Supported by Kodak Film. With thanks to Kevin Timmins at Gauge Film, Lydia Beilby for camera assistance on the ghost film shoot and to Mark Beever for the camera assistance, photo documentation and driving for Nathalie’s shoot, and to all the artists and contributors. Further thanks to Gillian Smith, Claricia Parinussa, Oliver Mezger, Sophia Hao and Peter Amoore at Cooper Gallery, Dundee and to the team at Dance Base in Edinburgh. Thank you to Peter Taylor at Berwick Film Festival and LUX Scotland. My thanks to Anne Petrie and Amanda Catto at Creative Scotland.

Compiled and edited by Alexander Hetherington. With a performance to camera by Michelle Hannah, and participation in the form of filmed episodes at a variety of locations and working with different subjects and references with Emma Balkind, Rowan Markson, Leah Millar, Rosie Roberts, Wendy Kirkup, Helen McCrorie, Nathalie de Briey (which also included a meeting with curator and artist Dr Peter Hill on the subject of lighthouses), Anonymous and a roll discussing sleep, and ‘blind’ actions in film, with recordings of works on paper by Catherine Street, additionally with the participation in the form of conversations on collaboration with Anne-Marie Copestake, slide film with Jennifer Wicks and Super-8 and 16mm and performance with Lars Schmidt and film camera workshops with Alex Millar, Lin Li and Maria Oliver-Smith discussing how film and its disciplines might relate to their practices and on film and sound with Mark Lyken. Conversations on the project happened with other artists but principal photography on these was abandoned or discontinued, for different reasons, though research shoots took place and are presented in miscellaneous materials, without origin.

A selection of films, music and readings entitled ‘Twin Eye’ was presented at ‘Studio Jamming’ at Cooper Gallery, including extracts from the opera ‘Now Eleanor’s Idea’ by Robert Ashley, the 16mm film ‘Wheels’ by João Maria Gusmão & Pedro Paiva and extracts from Judith Butler’s text ‘Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly’, September 2019; a second screening took place at ‘on being still and moving at the same time…’ at Dance Base, Edinburgh curated by Claricia Parinussa, November 2019. A discussion on film and collaboration took place during a LUX Scotland One-to-One with Peter Taylor at ESW, May 2019 while on the wider subject of 16mm film and adaptation I wrote a response to three films (‘Vivian’s Garden’, ‘Electrical Gaza’ and ‘Part One’ and ‘Part Two’) by Rosalind Nashashibi screened at Cample Line, by Dumfries and published online December 2019.

A film essay in the form of fragmented notes and observations was written December 2019 and January 2020 with the intention to perform the text live at a later date. This includes a text, ‘Talking, counting, blinking, noting [shouting out and letting be]’ by Glasgow based artist, writer and filmmaker Rosie Roberts.

16mm film, black & white and colour, 60 mins, 2020, film presented with a live text performed by readers and live sound, plus an online version in the form of a short trailer in reference to the work ‘TRAILER’ (2011) for ‘Piercing Brightness’ (2013) by Shezad Dawood.

‘Made possible with the financial assistance of Visual Artists and Craft Maker Awards: Forth Valley & West Lothian’.