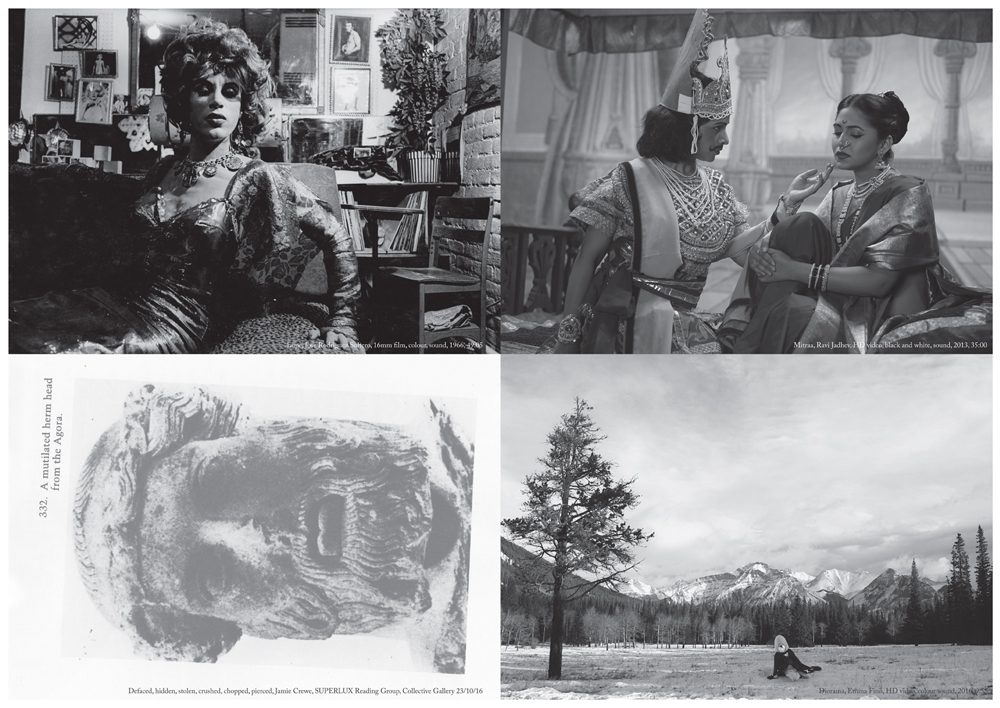

“The most beautiful room in the world”, Edinburgh Artists’ Moving Image Festival 2016

With texts on films, screenings and talks by Emma Finn, Derek Jarman, SUPERLUX, GLITCH Film Festival, Edward Thomasson, Raju Rage, et al, edition of 50, 2016, commissioned by EAMIF

Extract from Defaced, hidden, stolen, crushed, chopped, pierced’ Reading Group for SUPERLUX, Collective Gallery, 23 November 2016

A SUPERLUX reading group presented and programmed by Glasgow-based artist Jamie Crewe sought a wide-ranging consideration of the ways protest and its expressions might be made by disempowered people using implements that ‘deface, steel, hide, crush, chop or pierce’. Crewe lead collective readings of a number of interconnected texts flowing across these physical and mental acts of dispute or dissent. ‘We Want Truth Goldsmiths’ recounted feminist scholar Sara Ahmed’s resignation (“Resignation is a Feminist Issue”) from the School. During this reading defaced pages open with the allegation “John Hutnyk sexually harassed students whilst at Goldsmiths…” underneath the titles of his publications ‘The Rumour of Calcutta’, ‘Bad Marxism’, and ‘Critique of Exotica’. These handwritten notes forming an understated but direct transported objection on Hutnyk’s abuses of power then transitioned into sequences from Ahmed’s formal resignation statement. This presented evidence of the institution’s silencing of the experiences of sexual harassment and is bound accordingly into its neglect, complacency and complicity. The term ‘complaint’, and any acts of speaking out, Ahmed asserts were reframed and redefined. In acts of deliberate ‘reversal’ complaint was deemed to contravene or ‘infect’ the fabric of the institution. The presence of a dissenting female voice was deemed to invade Goldsmiths’ orderliness. Canadian poet and scholar Anne Carson’s seminal prose essay ‘The Gender of Sound’ from ‘Glass Irony and God’ published in 1995 was read in its entirety. Here Carson discusses a catalogue of historical philosophical and political evidence – from Sophocles to Gertrude Stein – on the female voice and its reception and interpretation: ‘It is in large part according to the sounds people make that we judge them sane or insane, male or female, good, evil, trustworthy, depressive, marriageable, moribund, likely or unlikely to make war on us, little better than animals, inspired by God.’ The female voice, Carson describes, is classified as animal-like, objectionable, fear-provoking, insane or out of control, in need of quarantine and muting, posing a threat to order, the anathema of self-control. Emphasis is given in her essay to the Greek notion of ‘sophrosyne’, or masculine virtues in voice and deed of moderation, temperance, clarity, sanity, disassociative of emotion while the female voice represents disorder, madness, witchery and the objectionable. Carson further describes methods by which the female voice and by extension the female genitalia are silenced and blocked, portrayed as ‘the closing of a door’ as representative of masculine civic duty: ‘[a] responsibility toward women is to control her sound for her insofar as she cannot control it herself.’ Moving from the page and text to the screen and voice Crewe then selects the BBC arts programme Arena presenting the actor Billie Whitelaw discussing her working relationship with Samuel Beckett on their preparations for her performance of the work ‘Not I’ which premiered at the Lincoln Center in New York City in November 1972. The piece, a violently paced monologue, which takes places in a pitch-black theatre space illuminated by a single beam of white light fixed on the actor’s mouth, was then screened. The voice relates through repetitive and fragmented sentences four incidents from the character’s, a 70 year-old woman’s life: lying face down in the grass, standing in a supermarket, sitting on Croker’s Acre in Ireland and in a courtroom. These incidents suggest a series of traumas which the character repeatedly identifies with and denies of herself: ‘…spared that…speechless all her days… practically speechless…even to herself… never out loud… but not completely…’ and ‘ …try to make sense of it … begging to the mouth to stop… pause for a moment… if only for a moment… and no response…’

Crewe’s closing passage for ‘Defaced, hidden, stolen, crushed, chopped, pierced’ was the production of ‘curse tablets’ or ‘binding spells’ made from strips of lead and implements to score, draw, piece or write upon, which could then be buried or thrown into wells or pools in order for the dead or the gods to transport the curse to their intended recipient. One such curse tablet, made from pitted, punctured and creased lead, on display in the British Museum reads: “I curse Tretia Maria and her life and mind and memory and liver and lungs mixed up together, and her words, thoughts and memory; thus may she be unable to speak what things are concealed, nor be able.”

Later in an exchange of emails between the day’s participants, with time to reflect on the events of the workshop allowed further references to come into play on its textures of the voice: pitched, silenced, unbound, urgent, choral, demanding, affected, questioning and, like the curse tablets, made solid. Crewe draws into the material trans activist and drag queen Sylvia Rivera speaking at the Gay Liberation Rally in 1973: ‘Y’all better quiet down!’, [https://vimeo.com/45479858] and Sharon Hayes’ show ‘In My Little Corner Of The World, Anyone Would Love You’ at The Common Guild in Glasgow, 8 October – 4 December 2016: ‘I was interested in reading aloud as a modality of thought. Sometimes we read out loud to ourselves to be able to hear better.’ It’s an image that aligns with the idea that the readers of these publications might ‘suddenly have an understanding of an identity which they thought before was behavioural or psychological or interior. They suddenly have something exterior.’ As we read something out loud to be able to hear it better and to be able to respond to it, so this piece creates a context in which you might be able to hear: ‘It was most important to me that the readers not characterise the I, and that they tried to find that place of just enough distance, to be present as themselves and also to allow the words to be addressed. Which is a kind of fine line.’ Published on The White Review, [http://www.thewhitereview.org/art/material-and-in-front-of-us-sharon-hayes/]

Meanwhile Joanna Monks from LUX Scotland suggested reading from African American feminist and civil rights activist’s Audre Lorde’s essay ‘The Transformation of Silence Into Language and Action’ first published in ‘Sinister Wisdom’ in 1978 and found in the collection ‘Sister Outsider, Essays and Speeches’ from 1984: ‘My silences had not protected me. Your silence will not protect you. What are the words you do not yet have? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence?… it is not difference which immobilizes us, but silence. And there are so many silences to be broken.’